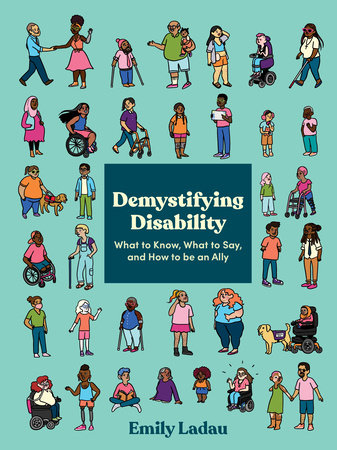

By Emily Ladau

Book review by Caitlin Meredith

Demystifying Disability by Emily Ladau is a practical guide to making our language, approach and practices as inclusive as possible for those with disabilities. With her wit, personal insight, and interviews with thought leaders in diverse disability communities, Landau invites readers to challenge our preconceptions about how people living with disabilities experience the world, and actively engage with expanding access and inclusion.

Much of her guidance is especially useful for mediators and other conflict professionals who want to make sure our practices are accessible for all.

Landau’s book challenges conventional assumptions about disability and explains the way ableism, rather than disability, limits disabled people’s access to “normal” life. She defines abelism as “attitudes, actions and circumstances that devalue people because they are disabled or perceived as having a disability.”

For people who don’t use wheelchairs, for example, the tendency is to feel sorry for people who do; that energy would be better spent, Landau points out, advocating for accessible bathrooms and subway elevators that are the actual obstacles to full participation in common life activities, rather than the disability itself.

Like racism, sexism and other forms of prejudice embedded in our culture, ableism is often hiding in plain sight for those it benefits. Through sharing her own experiences as a wheelchair user, and interviews with people with other types of disabilities, Landau connects the dots between common abelist comments (using mental illness conditions as insults, for instance) and the harm they do.

For conflict professionals, inclusion starts with our language – how do we talk about disability with parties and colleagues?

While Landau advises that the best approach is always to ask someone their preferred terms, she also provides a table of “best practice” language (use: disabled; don’t use: differently abled, handicapped or special needs) that is a great reference for everything from website content to conversations with parties.

Another aspect of accessibility Landau encourages readers to consider is how our offices, sessions, events and trainings (virtual or in person) might be experienced by people with a wide range of disabilities. She lists potential accommodations from providing written materials beforehand to designating seating areas for people with mobility disabilities to live captioning or interpreters for presentations.

As with language, Landau emphasizes that asking a disabled person how you can support their participation is the gold standard. Her suggested way of asking: “Hey, do you/does anyone have any accessibility needs to participate? Let me know how I can support you!”

Preparing for easy access should be on the preparation check list, not on the day of. To help with this, Landau provides great resources for organizations that provide free information and guidance on accessibility.

Landau is the first to point out that her book is a starting point for becoming an ally – or accomplice as some prefer – for reducing stigma, stereotypes and access for people with disabilities. She admits that she is in a constant struggle to update and improve her own blind spots within the varied disability rights communities. She provides many resources including organizations, books, videos and other media that explore, explain and advocate for increasing our understanding of a wide variety of disabilities to continue the process.