Why is it so important and how does the mediator use it to greatest effect?

Structuring the process is how we propose starting almost all elements of the Understanding-Based mediation process. Join us for our webinar on February 19, when Gary Friedman and Katherine Miller walk participants through the elements of structuring the process, discuss why it is such an important piece of the “How”, and answer questions from participants in this webinar.Shortly after getting married, Fatima and Martina merged their finances. Fatima, an engineer at a prominent manufacturing company, has always earned more than Martina, a part-time student, who supports herself as a barista. Martina may not earn as much as her partner, but she is a saver. On the other hand, Fatima is a spender. Due to Martina’s low income and Fatima’s spending habits, the couple live mostly paycheck-to-paycheck.

Since combining finances, Martina has been imploring Fatima to curtail her spending habits and contribute more to the savings. She has repeatedly tried to explain the need to build a safety net and invest in their future. Martina likes to broach the subject whenever Fatima treats herself with leftover income from her paycheck, attempting to make Fatima feel guilty for ‘yet another frivolous purchase’. In turn, Fatima becomes angry at Martina for criticizing her decision-making and impeding her autonomy. She lashes out and tells Martina to get a better-paying job if she wants to save more money. Ultimately, the argument devolves into attacks on their characters and sometimes the couple will not talk to each other for days. When their interactions ‘normalize’ after, this is because they are both bottling up their emotions surrounding this subject and they follow an unspoken agreement to tiptoe around the subject as much as possible. Months of this attack and retreat cycle has eroded their relationship and fearing they are on the pathway to divorce, they have agreed to engage with a mediator to help resolve.

“Disputing parties are usually fully occupied by the content of the problem…but recognizing how you talk to each other can be as important, sometimes even more important than what you talk about.” – Gary Friedman

Immediately, the mediator recognizes that Martina tends to dominate discussions and Fatima struggles to interject, until her simmering irritation bursts and her pent up frustration explodes on Martina. Fatima has internalized this as the only way she can be heard, the mediator realizes. This response does not incline Martina to listen though, and the mediator notes that this when the argument’s focus pivots to an airing out of grievances. The mediator knows that unless the couple changes how they talk to each other, it is unlikely that they will be able to resolve their dispute. For this to be successful, the mediator supports the couple in structuring the process around how they engage in this topic.

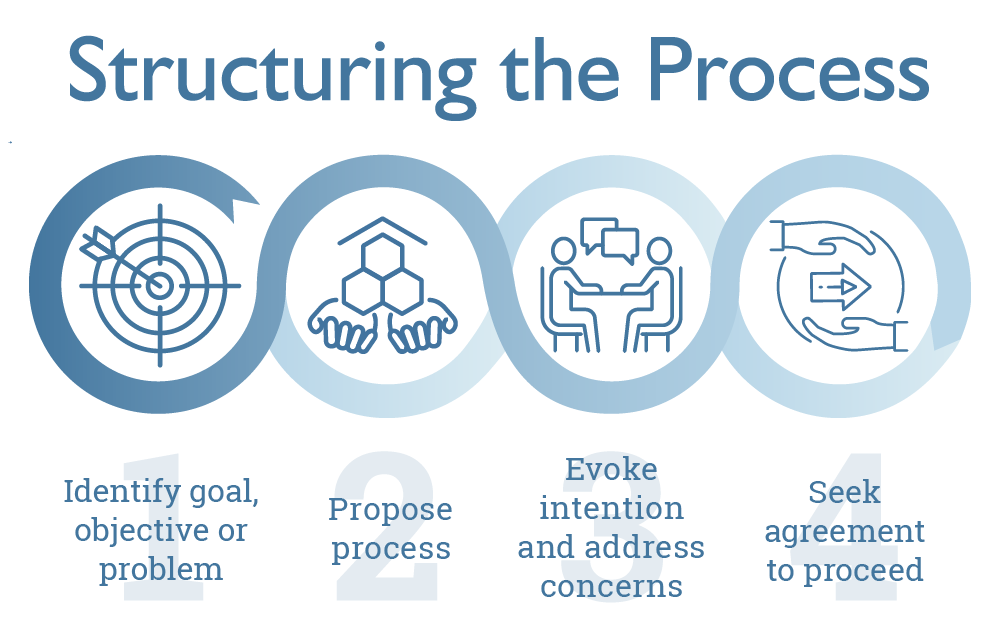

Structuring the process generally serves as the foundation upon which the Understanding-Based mediation process builds itself. The first step structuring the process is for parties to identify the goal, objective, or problem. Often, people give little thought to the process of how they will reach an agreement. Yet, frequently, it is not the ‘what’ of the problem that can derail the conflict resolution process, but ‘how’ the participants are engaging with each other. Martina and Fatima recognize their problem is rooted in their different attitudes towards money. Yet, while identifying the problem, the couple realize that their underlying issues—fears of financial insecurity for Martina and the ability to make autonomous financial decisions for Fatima—are inherently woven into the problem and also need to be addressed as well.

When both parties think about to talk to each other, the conflicting parties are better positioned to benefit from their own experiences while feeling like they are full participants who are invested in the conversation. “When I think about structuring the process, to me it starts with one of our core ideas…that we pay attention not just to the ‘what’ when people are talking to each other—what they’re talking about—but how they talk to each other,” notes Gary Friedman, co-founder of the Center for Understanding in Conflict (CUC). “A lot of conversations are unsuccessful because of the way the conversation takes place rather than necessarily even what’s said.”

Structuring the process also assists in leveling the playing field between the mediator and the parties so that when they talk, the parties aren’t blindsided by what comes next. In Martina and Fatima’s case, this will help ensure that Fatima is able to participate in the conversation, without having to bottle up her thoughts and emotions until they come cascading out all at once. Fatima’s higher earning power also creates an inequality in this dynamic and structuring the process can limit Fatima’s instinct to wield her income as a weapon against Martina.

Leveling the playing field is also instrumental in ensuring the mediator does not dictate what comes next and is running things. According to Katherine Miller, President of the CUC, when two parties are in conflict, “they each have half of the knowledge. They know what would work for them, but they don’t know what will work for the other person, because if they knew what would work for the other person, they wouldn’t be in our office.” What motivates Martina’s thriftiness is remembering the time when her parents lost their home due to medical debt. For Fatima, having a joint goal, such as saving for a home, is a more enticing prospect to save. “It’s [the mediator’s] job to put those two pieces together in the ‘how’ to have a conversation that works for both halves,” Miller adds.

“Each…has half of the knowledge. They know what would work for them, but they don’t know what will work for the other person…It’s [the mediator’s” job to put those two pieces together in the ‘how’ to have a conversation that works for both halves.”

— Katherine Miller

By coming together to evoke their intentions and address concerns, both Fatima and Martina are better able to understand the other’s perspective. Martina knows that tragedy can strike at any moment and just wants to be sure that what happened to her parents does not repeat itself with them. She is worried that longterm Fatima’s spending habits could leave them financially vulnerable. Fatima admits that she overspends and does want to better manage her finances, but she worries that if she approaches Martina for advice, her partner will try to control her income, not help her develop better habits. She is willing to contribute more, but she also does not want the pressure of their financial stability to depend overwhelmingly on her income.

The mediator suggests ways they can actively listen to each other and reflect before responding. With guidance from the mediator, Martina and Fatima agree to a process that includes equity in speaking times and guidelines for when and how the mediator should intervene if they start attacking each other. By actively structuring the process together, Fatima and Martina are better equipped to reach their own decision in how to resolve their problem, and not depend on the mediator to tell them what to do. Once this agreement is set and the couple move further into the mediation process, the mediator helps keep them on the path they have laid to reach the resolution, while leaving the agency with the party in conflict.

If participants do not take the time to structure the process, they can become disengaged and the pathway to resolution lost. “I think that balance of creating the mutually agreed upon container and the agreed upon center, which is the mediator, really gives the parties the support and the guidance and the leadership that they need to make a decision and to have the conversations that were previously too hard,” Miller comments.