Katherine Miller

The endgame can be one of the most challenging parts of the mediation process and preparations for the endgame should begin early on during the initial contracting process, as parties, attorneys and the mediator establish how they are going to work together. Good contracting sets up the end game among other things and provides parties with a structure to proceed when the going gets tough.

The endgame is challenging because it is where the rubber meets the road in the negotiation. We will have spent considerable time and energy exploring what is important to both parties (interests), understanding each party and assisting them to understand each other better and understanding the situation they face together including the differing perspectives of both parties in the early and middle game. Now, in the end game, we turn our attention to results and it is easy for the parties to slip right back into the conflict dynamic and positions they had at the outset. They key to a successful outcome, is to hold the established interests and their meaning while discussing the options and negotiating to a solution.

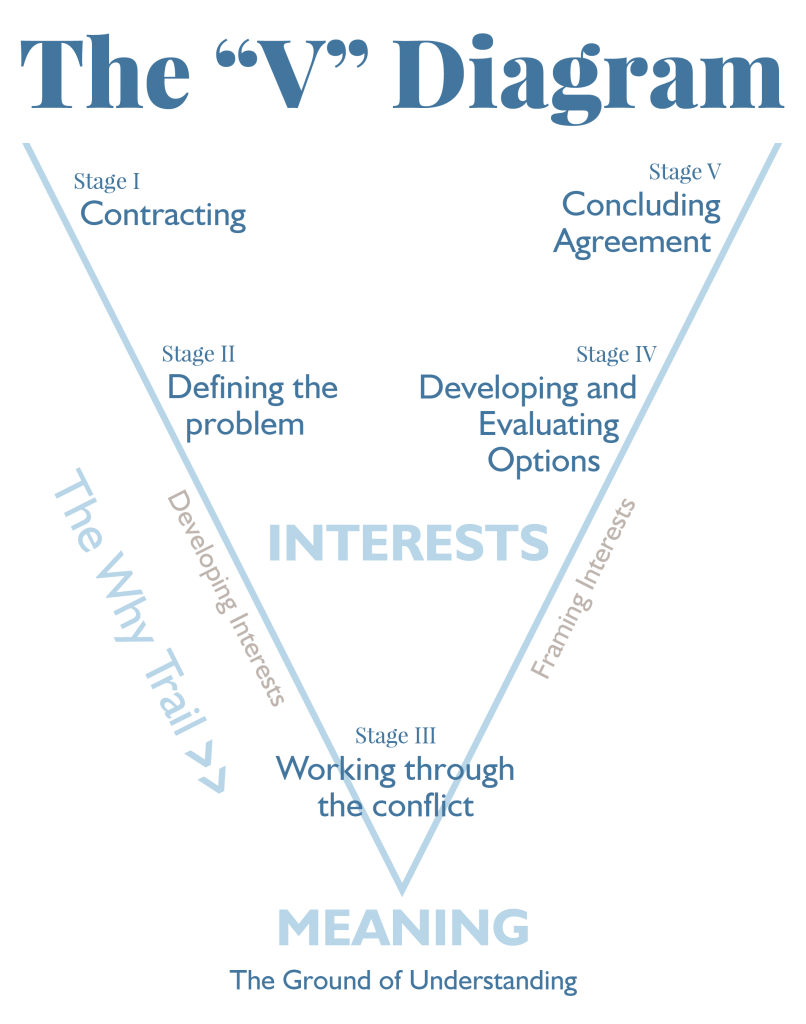

It is helpful to consider the “V” diagram as parties in conflict move from their initial positions to solutions. Oftentimes people come into a negotiation—and mediation is a form of negotiation—thinking that moving across the top of the “V” using coercion or compromise seems to be the fastest pathway to a solution. This belief is false. Attempting to move across the top of the V—directly to solution from positions—creates a superficial process that overlooks critical discoveries and considerations that can be uncovered while descending under positions, along the “Why Trail,” to understand interests, and even meaning, before ascending again toward solutions.

At the outset of mediation, following the “Why Trail” allows participants to go underneath the position and understand the why. “How does you position serve you?” “What is it that you are worried about?” “How do you see the problem?” “What is really important to you and why?” By posing a series of open ended and curious questions, participants are better primed to understand themselves, the situation they face and the party with whom they are more deeply in conflict. In turn, this deeper understanding allows the parties to build more meaningful and even more practical solutions during the endgame.

It is important to start thinking early on about what the group is going to do when they hit a difficult moment. Often people refer to this dreaded difficult moment as an impasse. Personally, I do not like the term “impasse” because it gives too much weight to a moment when the mediation feels stuck and therefore encourages the parties and even the mediator to give up when they feel stuck. When the group comes to a place where they feel trapped, it is useful if the mediator has somewhere to guide the group. It is very helpful in these moments to have established guidelines at the outset. It also helps minimize the possibility of reaching an impasse if everybody involved has an agreed upon “how” of having these conversations, which can be really challenging at times.

Ascension of the endgame

The endgame happens on the right side of the “V”, as participants frame the interests and develop options as they work towards solutions. At this point, the mediator should have a good understanding of all parties, what is important to them and how they see not only their own reality, but the reality that they share together. The parties should have a good understanding of themselves, perhaps a better understanding of the perspective of the other party/ies and a enough of an understanding of the problem they face to be able to understand the impact of various options. And now the time has come to develop a deal.

It can be dismaying for new mediators to discover that when parties start brainstorming options they first go to their original positions. This is completely natural. They have rehearsed those positions so many times and getting them out is a way for them to relax. The key is to stay in brainstorming mode when this happens and not allow the parties or yourself to move into evaluation mode.

The challenge to the endgame is to figure out a way to keep the parties, mediator, and attorneys, grounded in the interests and what is important to each person while discussing the options for potential resolution. One way to do this is to encourage the parties to think about options that create value – what are creative ways for the parties to view their situation that permit them to add value to the situation and ease the fear of a zero sum game, where if one person wins something, the other must necessarily lose. Perhaps one of the parties has something else they can bring to the table, or another benefit. There can be overlooked resources or different ways of seeing the problem that allows more value to be created and creates more room inside the problem to look at it in different ways. When more value is created, it can be applied to the problem in a way that gives the possibility of a better resolution.

There are a couple of things to watch out for and some concepts that can be helpful in the end game:

BATNA and WATNA

If the parties in conflict are struggling to work out their problems in mediation or negotiation, sometimes it is helpful to consider the Best Alternatives to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) and the Worst Alternatives to a Negotiated Agreement (WATNA). What are the alternatives the parties have to resolving the conflict in mediation? It can be helpful to get perspective on the issues by considering the other possibilities and creating a “real world” context.

One person’s BATNA can be another person’s WATNA. For example, for a couple considering divorce, one person’s BATNA may be “do nothing,” stay married and muddle through. For the other person, this is the WATNA. Considering the WATNA and BATNA is about understanding what the parties will do if they can’t work here. What are their options? What are their costs? Not just monetarily either, parties need to consider costs in terms of time, emotional expenditures, distraction disruption, costs to children, etc.

The BATNA and WATNA are important in terms of the endgame because it helps people evaluate how good or bad their options are. It allows the parties to create perspective on the options that they are thinking about. It is, however, important not to use the BATNA/WATNA to coerce parties into a resolution they do not embrace and for that reason we do not dwell on these concepts in the Understanding-Based model.

Red Herrings

When a red herring is brought up in mediation, it can create a distraction from what is really going on and keep people from talking about the real issues. During the endgame, a red herring can be an attempt to cover what is really going on underneath the surface that is stalling the process.

Red herrings are particularly common in divorces. For example, about a decade ago, a friend requested a consult with her friend who was getting divorced. This woman was going through a very difficult divorce with a challenging soon-to-be-ex-husband. The parties had almost completed their mediation agreement, when the husband suddenly insisted that he wanted some the pink towels that the wife had bought some years prior. The woman could not understand why her soon-to-be-ex was so obsessed with wanting the towels. This red herring ended up being about control. The woman was getting the house, the kids spent most of their time with her—the man felt like she was getting control over the life they had together. Once I laid out the explanation to her, it immediately clicked and she agreed to let him have the towels.

Red herrings can be tricky to deal with. The mediator is well-served to approach it with curiosity—what is really going on for the party raising it—and not with judgment or frustration.

Second Thoughts and Waffling

The outcome of a mediation is not always going to be a resolution. That does not mean the entire process was a failure and it can become problematic if the mediator feels their success is based on whether or not a party reaches an agreement.

It can be coercive if mediators attempt to pull parties towards the resolution in the endgame—if anything, the parties should be pulling the mediator towards the resolution. Moreover, parties are more likely to have second thoughts and start waffling if they are feeling pulled. The mediator can best help parties evaluate the options if they are agnostic as to whether they reach a resolution or not. With this neutrality, the mediator can help the parties evaluate their BATNA and WATNA and that can help create more certainty in the parties (or they can decide not to agree in this moment).

Conclusion

The endgame is not about mediator—or mediation—success. Even if the mediation does not result in an agreement, the parties are able to use those conversations and move to a different process to seek resolution. The conversations from the mediation will be useful ultimately to help people better understand the situation and themselves.

The results of the endgame can be strengthened throughout this entire process by going deep using the “V” method and working with the parties in conflict to create and claim value. Exploring BATNAs and WATNAs as well as cognizance of red herrings can help keep parties from getting stuck when difficult conversations arise.

Katherine Eisold Miller is a Collaborative Lawyer and mediator with a practice located in Westchester County NY and New York City. She serves as the President of the Center for Understanding in Conflict. Katherine is immediate past president of the New York Association of Collaborative Professionals. Katherine is author of the New Yorker’s Guide to Collaborative Divorce (2015) and co-Author of the #1 Amazon bestseller A Cup of Coffee with 10 of the Top Divorce Attorneys in the United States (2014).

Interested in learning more about this topic? Join our upcoming webinar with Katherine Miller and Gary Friedman: