By Kayla Hellal

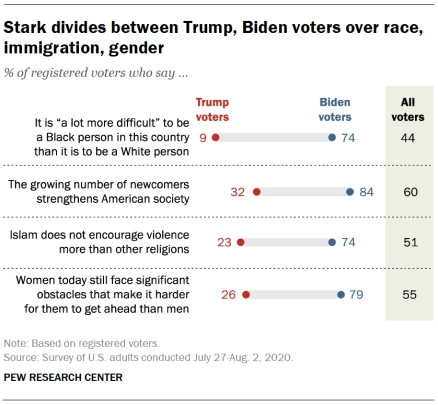

We live in a polarized world. This is particularly true in today’s U.S.A., where people divided along political lines have markedly different stances on a wide range of social, economic, and environmental issues. Our own views of the world can now be supported by the narratives presented in cable news networks, algorithms compiling our social media feeds, the websites we visit, and other forms of media that we consume to stay “informed” about our world.

The sharp contrast in understanding became even more poignant over the summer, as the wave of protests demanding Americans reckon with the injustices carried out against people of color hit a fever pitch in the wake of the death of George Floyd at the hands of police. Americans seemed to divide into two main camps—supporters of Black Lives Matter and those supporting police and law enforcement institutions. Over the summer, the evening news led with footage from cities all across the country of peaceful protests, buildings burning, clashes, and news conferences from law enforcement agencies.

Then, on a Sunday in late August, videos emerged on social media of a white police officer shooting a Black man in the back seven times in Kenosha, Wisconsin. As the sun set, protesters gathered at the city’s neoclassical stone courthouse. Later that night, dump trucks blocking the courthouse were set on fire and over the next two days, thousands gathered in peaceful protest during the day, while at night businesses were looted and burned. On the third night, militias swarmed the town, with one person from Illinois killing two protesters from Kenosha.

The events that unfolded in Kenosha struck a chord with Americans and the town became the token of suburban America. For me, this was deeply personal. Kenosha is my home town and I now live just 40 minutes to the north in Milwaukee, which itself is notorious for its ranking as the worst city for Black Americans and the most segregated city in the nation. Overnight, Kenosha was the focal point of all my interactions with family, friends, and my networks. My social media feeds were flooded with videos, photos, and stories from the city I lived in for the first 18 years of my life. Suddenly, I was at odds with lifelong friends and family members.

I realized this would be a good opportunity to try out some of the skills I have been learning since joining the Center for Understanding in Conflict’s team earlier this year. I had a lot of feelings about this issue to process, but I also needed to understand the perspectives and experiences of others. I headed down to Kenosha to talk with a civilian, Tina, and a cop, Chris. Using looping —a method of listening with the goal of understanding—I learned about their experiences.

Going Down the Why Trail and The “Internal V”

A fundamental part of the Understanding-based Model is more deeply grasping why a particular issue is so important. By going down the Why Trail, we find out what is below the surface in a conflict. By using the “Internal V” model to pay attention to our inner reactions, we are able to be more open to understanding someone else and connecting to them. I decided to try these tools to better understand my own judgments and feelings.

Why was the unrest in Kenosha so important to me?

Because it is my home town, a place that I consider safe and where so many people I care about live. I have experienced civil unrest while living in post-revolutionary Tunisia and more recently in Chile, where I was tear gassed and chased down by military police just for being there. Yet, for me, Kenosha has always been a safe and secure place. I have been watching the world unravel firsthand for years, yet never did I anticipate curfews and militia in my home town.

Why should I care about this issue?

White privilege—my entire life I have benefited from it, and it comes at the expense of people of color. Justice and equality are core components of my value system and identity, and I have the responsibility to be part of a collective effort to help balance the scales.

Why do I want to empathize more with Jacob Blake than the police officer?

My husband is a person of color, and my little brother is biracial, half Black and half white. When I heard about Jacob Blake, I couldn’t help but immediately think of my family, then of Blake’s family. When I hear the names of the long list of people of color killed by the police—such as Joel Acevado, Dontre Hamilton, or Sylville Smith—it brings such feelings of grief at thinking of all that is lost.

As I worked through my feelings, my fear and grief culminated into rage. No matter where I go in this world, injustice strips away the potential of humankind. People are dying as we alienate each other, and none of us is better for it in the end.

Yet, I have this deeply rooted optimism, and even in all of my negative emotions, I cannot help but think of the potential that springs from people coming together to solve problems. After all, a fundamental concept in the Understanding-based model is that the people who are in conflict are the ones who carry the solution.

Articulating my judgments, and their companion emotions, offers a clarity in my own understanding of the issue. Being able to name the emotions inside myself makes it easier to empathize and connect with others, such as with Tina and Chris as they share their experiences.

Looping

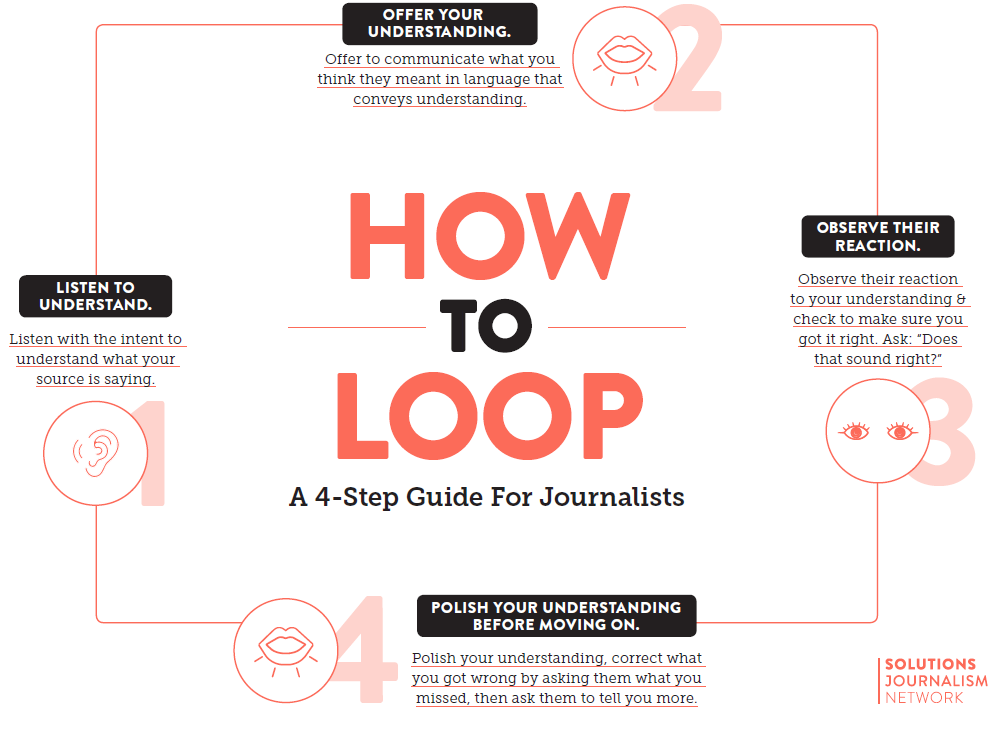

Looping is a technique that helps focus dialogue and develop understanding during difficult conversations. Initially, looping was developed for mediation; however, over the decades, it has become a useful tool in a variety of professions, including journalism.

Looping is a four step process that includes: listen to understand, offer your understanding, observe their reaction, and polish your understanding before moving on. Looping requires that you are listening with the intent of understanding what they are saying. Journalist Amanda Ripley, who uses looping when she interviews sources, stresses that when looping, “don’t think you’re going to persuade somebody that they’re wrong. It’s to learn something you didn’t know.”

When developing understanding, it is critical to listen more and better. This includes asking questions about how a person feels as they talk about the issue, as well as where their emotions or position are coming from. Additionally, asking questions such as “What do you think the other group thinks of you?” helps expose people to the other tribe, which also provides pivotal foundation when developing understanding.

Deepen the conversation by going beneath the problem by asking questions that get at motivations. Questions such as “Why is this important to you?” or “How has this conflict affected your life?” provide opportunities to go down the why trail and truly understand what is important to the person you are talking to.

When working through complex issues, asking questions to amplify contradictions, such as “Where do you feel torn?” or “What is oversimplified about this issue?” provides opportunities to investigate tension. It is important to notice the dynamic for further information.

It may also help to ask questions for the speaker to widen the lens. Asking questions such as “How do you decide which ‘facts’ to trust?” or “What is dividing us as a country?” provides insight into how the person constructs their reality. This in turn supports autonomy and honors connection.

To counter confirmation bias, ask the speaker to talk about what they know about the “other side.” Ask them to help you make sense of something being said by the other side. This process creates space to recognize that others also own the conflict.

Ripley notes that “we want to believe deeply if we share facts, people will believe us and agree.” Yet, that has not been working, and Ripley comments that the only way she can be useful when engaging in high conflict conversations is to be genuinely curious. “If you’re genuinely curious, people around you can get curious and can tell people stories that spark curiosity and challenge their assumptions…but it is impossible to feel curious when you feel threatened.”

In my interviews with Tina and Chris, I apply looping to ensure my understanding of their experiences to the unrest in Kenosha. As they share their experiences, I prompt them to elaborate with questions geared to help ensure that I understand their perspectives and I clarify my understanding with them throughout the process. Often, I repeat back what I have heard, and ask if what I am repeating is accurate. Along the way, they correct or affirm. Below are excerpts from our conversations using looping.

Tina

Tina is warm and bubbly. She studies communication at the local technical college while working full time at a local family-owned shoe retailer. She is also expecting her first child. Before the interview, she excitedly shows me the freshly painted galactic-themed nursery in the home she shares with her partner. Tina is also one of the 17.6% of Kenoshans who identify as Hispanic or Latino.

She is sitting on the far end of her couch, her right hand resting on her baby bump as I ask her to talk about what happened in Kenosha. “Well, I saw the gentlemen get shot in the back seven times, I saw the video of that. Somebody shared it on Facebook and it autoplayed on my feed and it was pretty jarring to see.”

Tina looks off to the left and gives her stomach a small rub as she continues. “I’d never seen anything like that happen here ever. You see it happen other places, but when you see it where you live, it’s kind of messed up to think about. I immediately thought, this is going to hit the fan. And it did,” she concludes with a curt laugh.

When I ask her to clarify what she means by “messed up”, she comments, “We’ve been seeing this stuff happen, but it felt not as real because [it was] something you don’t think is going to happen where you live.” She felt Kenosha was a safe place, although “there’s a pretty clear divide in this town where the nice and bad areas are.”

As she extrapolates on her experiences, she notes that for her, it “makes sense why it happened.” She comments on how the local government works to appease one demographic in particular—“white people over 40.” She mentions a local councilman who had tried to start a coalition for young people, but other council members “shut it down” right away. Furthermore, she comments that “parts of town have no resources. There are no groceries on the east side of Green Bay [Road] and you’re screwed if you don’t have a car.”

When she watched the video of Jacob Blake, she couldn’t help but wonder if the police could’ve handled it differently. Tina recalls seeing six cop cars pull up to apprehend somebody in her neighborhood. She muses about what a weird spectacle it was to watch a dozen cops apprehend one individual, and whether that many were necessary, or if there could have been a better way of handling the situation. “Like with [Blake], couldn’t the four officers have just dog piled him? There’s gotta be a different way.”

She speaks a little more quickly as she adds, “I’m not anti-law, I’ve always respected cops in town, but I know [about] racial scandals within the KPD [Kenosha Police Department]—well, heard allegedly. I’ve never had a personal problem with them.” She is very conscientious about relating the things she hears, and repeatedly as she shares her insights, notes that she takes things with a “grain of salt.”

Again, she refers to her preconceived notion that what she sees in the news and on social media won’t happen where she lives, to her. However, she adds, “being a minority, it’s always in the back of my head—what could happen. I haven’t encountered too much but I’ve always felt on edge, really on edge, where could this go and what could happen?”

Despite this jarring experience, and the fear and anxiety tied to her reality, Tina is also empathetic, acknowledging that the police handle too much and this is a contributing factor part of a larger, more complicated issue.

Nor does the unrest hinder her optimism, a trait that she is known for among her friends. “There are a lot of fundraisers for uptown and downtown. I saw the community coming together to try and heal,” she says. She criticizes a Buzzfeed article accusing the community of whitewashing BLM when painting the murals. “There were a lot of messages supporting BLM and I personally knew a lot of the people who were both protesters and members of the cleanup.”

Chris

Chris joined the Kenosha police department earlier this year—before George Floyd’s death became a tipping point in public opinion about policing. He is a likeable guy who is friendly, helpful, and handy. Throughout our conversation, he maintains a confidently calm demeanor, which I imagine serves him well in policing. Like 89% of his colleagues on the police force, Chris is white.

Coming into the interview, I was aware that I carried bias against police. Typically, I would approach this situation as more of a debate and would equate my silence to complacency. I recall Ripley explaining that “you don’t have to argue or agree, there’s this third way.” When we had spoken, she had highlighted the importance that looping is not equivalent to complacency: “At first, I thought if I didn’t argue, I was complicit and part of the problem, but it doesn’t work that way…When you loop people, they don’t mistake it for agreement—it’s more like you’re listening and trying to understand.”

Like civilians, Chris learned about the shooting from the video spread across social media in the hours following the incident. His initial thought was that “this was another big shooting that you know happens as an officer. [It] didn’t feel too out of place.”

When I asked him about his feelings the first night, he commented that he went to bed nervous about work the next day. On the morning after the shooting, he got to work and saw 70 calls pending when there are normally zero. “It was shocking to get to work and having to take burglary calls, finding six businesses in a row looted. I must’ve taken 20 calls that day,” he recalls.

According to Chris, “On the second night, things got more serious” and a curfew was declared. When it came to how he felt personally, he noted that “it was a very shaky feeling hearing people who I know that were in the military that this was how it felt when they were in Iraq—with the fence and the National Guard. It was kind of jarring.” Professionally, however, he felt secure with the National Guard surrounding the police station and courthouse. With their support, he was able to focus on doing his job—even with all of the unrest, there were still car accidents and other things that happen every day that police deal with.

As Chris talks about the surrealness of the “warzone” comparisons, I cannot help but think of my own experiences with police during periods of unrest over the years. I recall the day when citizens burned several police stations in Tunisia, and my seething anger when the police waved their gun at my car as I drove a coworker home that evening. I also remember the Chilean national police standing in a line facing the yells and taunts of protestors, minutes later spraying us with tear gas and shooting rubber bullets into the crowd. And the police standing in line outside the Milwaukee police station, watching us in silence as we chanted and jeered. I realize that in my own experiences coupled with a desire to understand the experiences of people of color and law enforcement, that I compartmentalized the police as the “other”, subsequently dehumanizing them in the process. Never before had I thought about what they were feeling, the people behind the riot shields, the families anxiously waiting for them at home.

Chris does not directly know any of the officers involved with the shooting. However, he notes that there is still “a brotherhood that comes along with this career and it strengthens my concern for the officer, what happened to him, and the situation he goes through.” For Chris, a few hours difference could have meant he was among the responders to what seems to be a normal call that suddenly turns into international news.

One of his most surprising moments from this entire experience came when he was responding to calls in uptown, where five buildings had been burned down. The images shown on the national news were mostly from downtown Kenosha, which are predominantly white-owned businesses. Less common in circulation were the photos from uptown, where most of the businesses destroyed are owned by people of color. Uptown is also a higher-crime area and the police are frequently present.

While responding to the calls, the officers received “overwhelming support from people in a neighborhood that were well aware of us as law enforcement officers. People were coming up and thanking us—people who were angered at what happened to the neighborhood.” This unexpected support felt phenomenal and he also realized that even though this was a high-crime area, the people loved their neighborhood and phenomenal people lived there. Chris explained that the shops that burned left people in the neighborhood nowhere nearby to get their basic needs. “Transit even shut down, so it just added an extra step to the issues,” he adds.

Chris comments that his job gives him a close up understanding of what people are going through. “It was difficult to hear them talk about and to understand their struggles,” he admits. He talks about taking reports for businesses that don’t have insurance and wondering how they will be able to come back. He acknowledges that as a white man he is not going to be able to fully understand their experiences. “It’s hard not to be biased, but I try to keep an open mind. I try to do my best and understand them and their feelings.”

He is earnest as he talks about Uptown, his genuine concern for the area etched in his voice. “In a neighborhood like Uptown, that’s such a neighborhood where it’s close knit and people stick to that neighborhood and it might not have the ability to recover. It worries me what that neighborhood could turn into. Hopefully it will rebuild from the ashes and not turn into a block of empty buildings that could attract more trouble.”

Conclusion

As I prepped Tina and Chris for their interviews and we were making small talk, Chris shared a story from while he was on duty during the protests. All dressed in riot gear, he watched a Black Lives Matter protester and a Blue Lives Matter protester get into a verbal argument. They started yelling at each other and the officers worried the situation would turn violent. Suddenly, the pair stopped yelling and one of the protesters offered the other to get a beer and talk about their views. It de-escalated quickly, much to the surprise of Chris and his colleagues. The fact that Kenosha was the backdrop, the town with more bars per capita than anywhere else in the U.S.A. (or so the local legend goes), it is only appropriate that their first agreement involved beer.

For Tina, Chris, and myself, we all found this experience jarring for different ways. Yet, we also all found optimism from our varying experiences, commonalities that help bridge our divides. Since my interviews, I have found that using looping has been beneficial in having difficult conversations with family and friends, especially with those whose opinions fall farther from my own spot on the spectrum.

As we bid adieu to the infamous 2020, the divisions that define today’s America will continue to challenge our conversations with our family, friends, and acquaintances. Even as this dreadful year concludes, prominent polarization seems to only increase its entrenchment. If we can practice understanding, perhaps we can weave back together our communities and our world so our society can finally create the spaces for freedom, equality, and justice for all.